| Comparison of Random Effects vs. Marginal Models | ||

|---|---|---|

| Feature | Random Effects Model | Marginal Model (GEE) |

| Interpretation | Subject-specific | Population-averaged |

| Handles Overdispersion | Yes (via latent effects) | Yes (via robust SE) |

| Computational Complexity | Higher | Lower |

Exploratory analysis

Model-based Geostatistics for Global Public Health

Overview of topics

- How to explore relationships with count data

- How to use a non-spatial model for mapping

- How to handle spatial data in R

Example: Riverblindness in Liberia

- How to explore relationships with count data (binary and aggregated counts)?

- How to model non-linear relationships?

- How to use a non-spatial model for mapping?

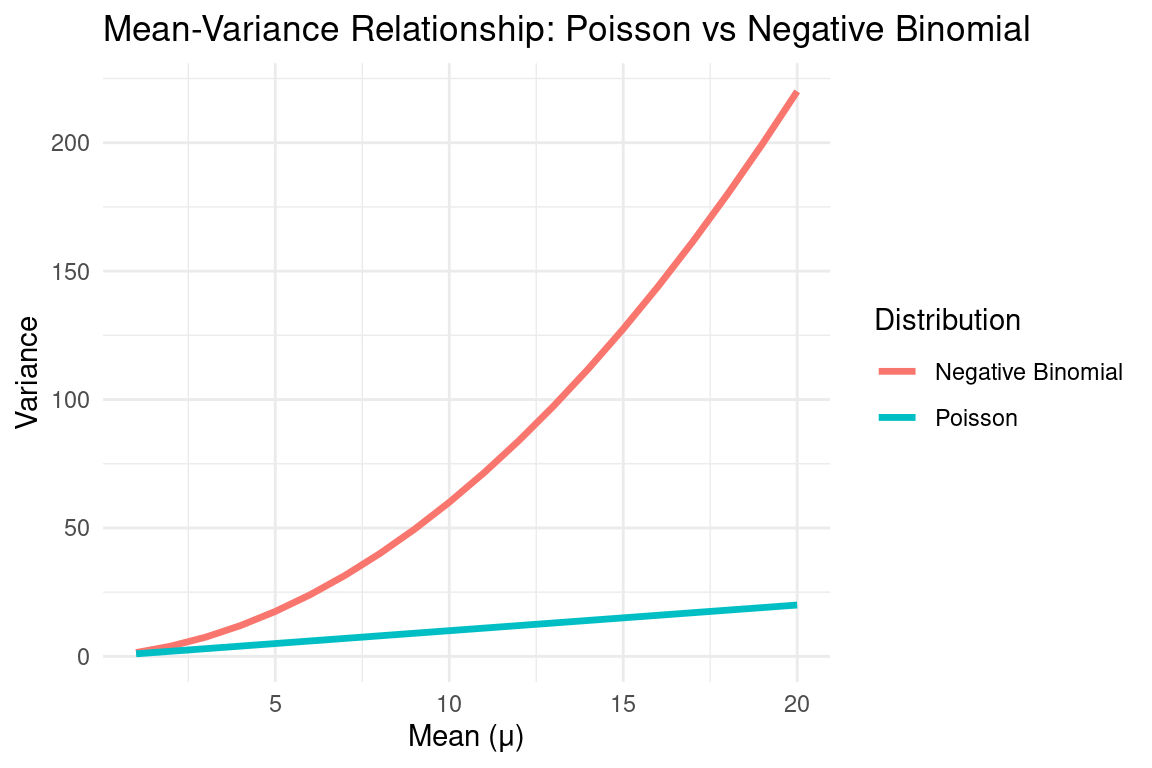

Overdispersion in Count Data

- What is overdispersion?

- Occurs when the variance of count data exceeds the mean.

- Violates the Poisson assumption:

\[ \text{Var}(Y) = \mathbb{E}(Y). \]

- Why does it matter?

- Standard models (e.g., Poisson regression) underestimate uncertainty.

- Leads to overly optimistic confidence intervals and p-values.

Example: Negative Binomial Distribution

A common solution for overdispersed count data.

Extends the Poisson distribution by introducing a dispersion parameter \(\alpha\):

\[ \mathbb{E}(Y) = \mu, \quad \text{Var}(Y) = \mu + \alpha \mu^2. \]When \(\alpha = 0\), it reduces to Poisson.

Random Effects Interpretation:

- The Negative Binomial can be interpreted as a Gamma-Poisson mixture.

- The Poisson mean \(\mu\) is drawn from a Gamma distribution, introducing extra variability.

Random Effects Models for Overdispersion

- Overdispersion often arises due to unobserved heterogeneity.

- A solution is to introduce random effects that account for latent variability.

. . .

- Random Intercept Model:

\[ Y_{ij} \mid Z_i \sim \text{Binomial}(p_{ij}), \quad \log\left\{\frac{p_{ij}}{1-p_{ij}}\right\} = \beta_0 + d_{ij} \beta_1 + Z_i. \]

. . .

- \(Z_i \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma^2)\) captures between-group variability.

. . .

- Leads to extra variability in counts, addressing overdispersion.

. . .

- Connection to Negative Binomial:

- If \(Z_i\) follows a Gamma distribution instead of Normal, the model is equivalent to a Negative Binomial.

Marginal Models for Overdispersion

An alternative to random effects models is using marginal models.

Instead of modeling subject-level variation, these models estimate population-averaged effects.

Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE):

- Does not assume a specific distribution for random effects.

- Uses a working correlation matrix to account for within-group dependence.

- Robust standard errors help correct for overdispersion.

Choosing Between Models

. . .

Example 1

- A clinical trial measuring blood pressure at multiple time points for patients in different hospitals.

- Why Use Random Effects?

- Each patient has their own baseline blood pressure that varies.

- A random intercept accounts for individual differences.

- If hospitals have different treatment protocols, a random hospital effect can be included.

- Each patient has their own baseline blood pressure that varies.

. . .

Example 2

- Study Design: A population-wide study on whether a new influenza vaccine reduces hospitalization rates.

- Why Use Marginal Models?

- Interest is in the population-averaged effect of the vaccine, not individual variation.

- Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) account for correlation in repeated measures without assuming a specific random effect structure.

- Interest is in the population-averaged effect of the vaccine, not individual variation.

A class of generalized linear models

Assumptions:

. . .

- \(Z_{i}\) are i.i.d. random variables;

. . .

- \(Y_{i} \mid Z_i \sim f(\cdot)\) belongs to the exponential family;

. . .

- \(E[Y_{i}\mid Z_i] = m_i \mu_{i}\) and \(\text{Var}[Y_{i} \mid Z_i] = m_i V(\mu_{i})\);

. . .

- \(g(\mu_{i}) = \eta_i = d_i^\top \beta + Z_i\);

. . .

- \(Y_i \mid Z_i\) are mutually independent for \(i=1,\dots,n\).

Parameter Estimation

Let the \(Z_i\) be i.i.d. Gaussian distributions with mean zero and variance \(\sigma^2\).

Likelihood function

The vector of unkown parameters is \(\theta=(\beta, \sigma^2)\) \[ L(\theta) = \prod_{i=1}^n \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} [Z_i] [Y_i \mid Z_i] \: dY_i \]

. . .

- Estimation Method

Maximize the likelihood using the Laplace approximation (glmer in the lme4 package).

. . .

Hypothesis Testing

- Obtain \(\hat{\theta}\) (MLE).

- Obtain \(\hat{\theta}_{0}\), the MLE constrained by fixing \(p\) values of \(\beta\) to 0.

- Compute the log-likelihood ratio:

\[ D = 2(\log L(\hat{\theta}) - \log L(\hat{\theta}_0)) \sim \chi^2_{p} \]

- P-value: \(P(D > D_{obs} \mid H_0)\)

. . .

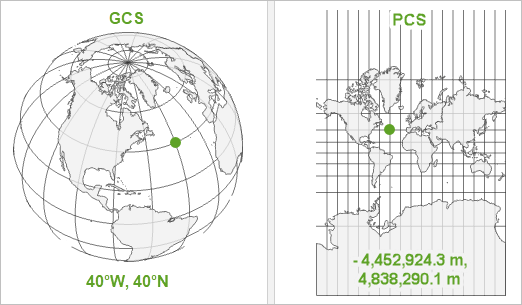

Coordinate Reference Systems (CRS)

- A CRS defines how spatial data is projected onto the Earth’s surface.

- Two main types:

- Geographic CRS (Latitude/Longitude, e.g., WGS84)

- Projected CRS (e.g., UTM, which uses meters for measurements)

Computing Distance

Distances in Geographic CRS (Lat/Lon) require geodesic calculations (e.g., Haversine formula).

Projecting to UTM allows for Euclidean distance calculations in meters.

Conversion to UTM in R:

library(sf) points <- st_as_sf(data.frame(lon = c(-0.1, -0.2), lat = c(51.5, 51.6)), coords = c("lon", "lat"), crs = 4326) points_utm <- st_transform(points, crs = 32630)

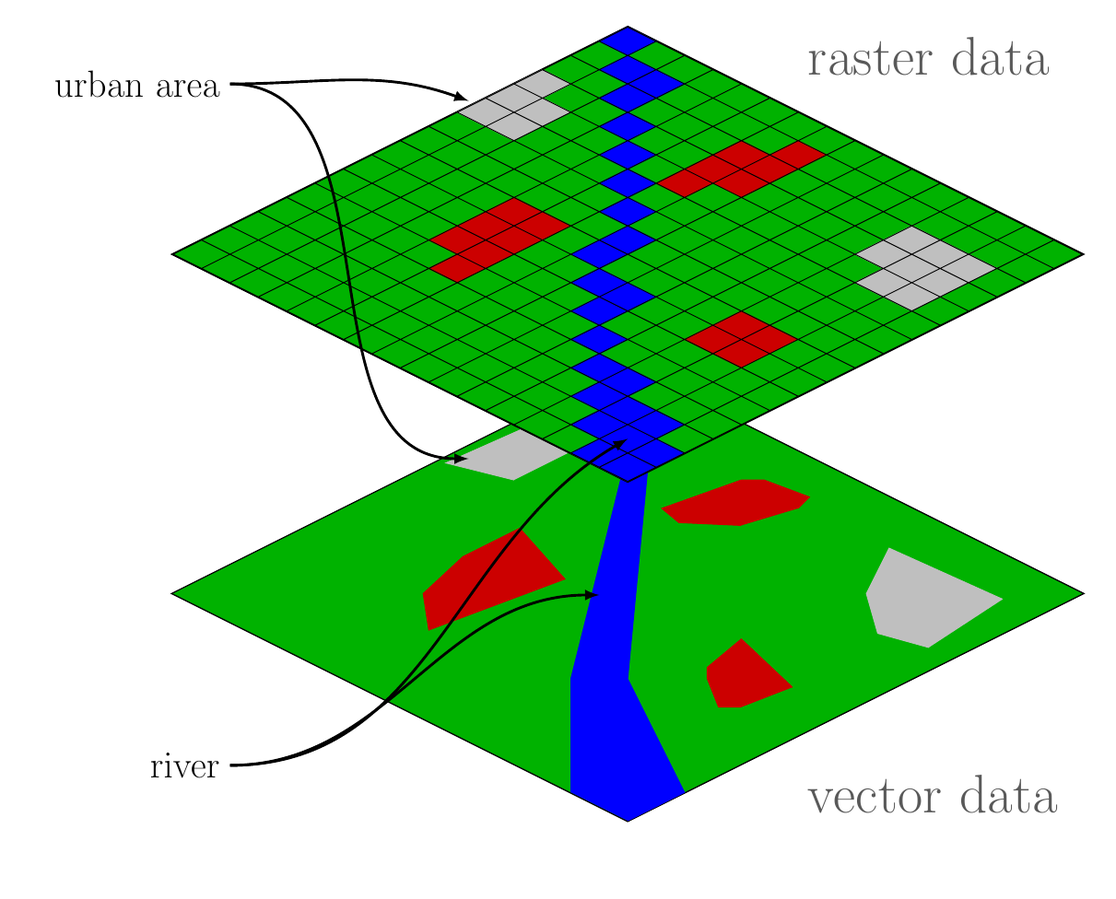

Spatial Data Formats

- Shapefiles:

- Vector data format for storing geometries (points, lines, polygons).

- Commonly used in GIS applications.

- Raster Files:

Grid-based data (e.g., satellite images, elevation models).

Each cell has a value representing an attribute (e.g., temperature, elevation).

Mapping with covariates only

Consider the following GLMM for the Liberia data on riverblindness. \[ \log\left\{\frac{p(x_i)}{1-p(x_i)}\right\} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \log\{e(x_i)\} + Z_i \] where \(e(x)\) is the elevation in meters at location \(x\) and \(Z_i \sim N(0,\tau^2)\) i.d.d.

. . .

Question: How can we use this model for mapping?

. . .